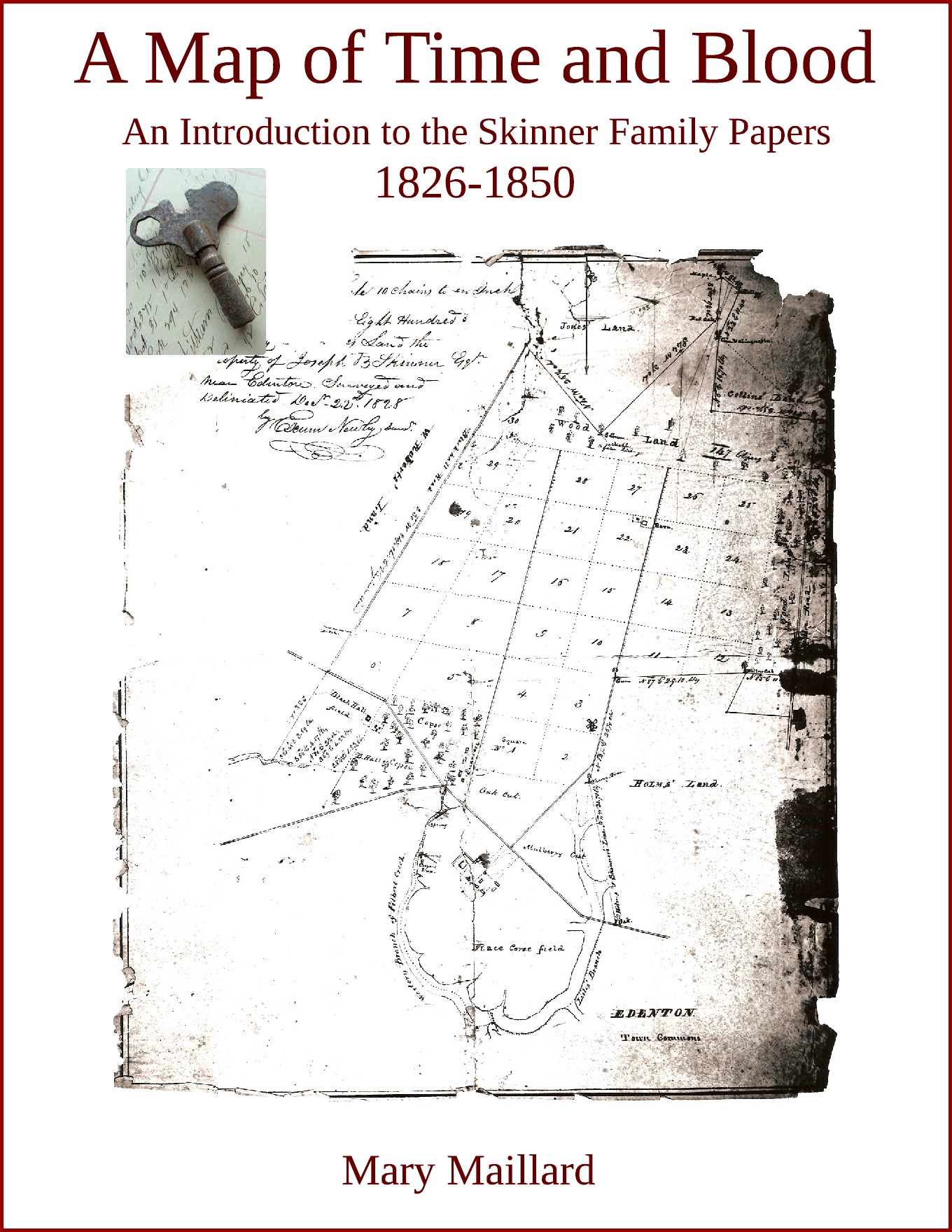

Sample Chapter

~Beginnings: the Lowthers~

Joseph Blount Skinner’s house on the Court House Green, Edenton, North Carolina. Photo by Mary Maillard.

Thomas Harvey Skinner insists in his memoir of his brother – quite disingenuously – that Joseph Blount Skinner’s marriage to Maria Louisa Lowther had nothing to do with his success. Tom claims that the union did not advance his brother’s career or add to his wealth, and that “Joe B” attained his substantial holdings purely by his own hard work and intelligence.[1] In fact, Maria Lowther provided Joe B with not only valuable access to her social network but also a tidy package of property.[2]

Maria Lowther Skinner’s father, Tristrim Lowther, and her aunts, Margaret Lowther Page and Barbara Lowther McLean [McLaine], considered themselves a literary family. They had acquired a vast library from their father, later incorporated into the Page-Saunders private family library in Williamsburg – a home that Maria’s young son, Trim Skinner, often visited while a student at the College of William and Mary 1838-1840. According to family legend, Tristrim Lowther’s parents, William (1729-1795) and Barbara Gregory (1738-1794), named their son Tristrim after Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy (published 1759-1769) and they also gave him the nick-name, “Trim,” after a servant character in the same novel. In fact, Tristrim Lowther was named after an uncle of the same name who died in North Carolina about the time of his birth in 1757.[3]

Barbara Gregory Lowther’s social sphere in England included Fanny Burney, author of Evelina: the History of a Young Lady’s Entrance into the World, three other novels, eight plays, and twenty volumes of journals. Barbara’s Edinburgh first cousin, Dr. John Gregory, penned the classic, popular guide to conduct and manners, A Father’s Legacy To His Daughters, published in 1774. Her daughter Margaret Lowther’s closest girlhood friends, Beulah and Susan Murray, were the sisters of Loyalist Lindley Murray (1745-1826), the textbook writer known as the “Father of English Grammar.”

Margaret Lowther Page (c1762-1835) was a noted poet who counted St. George Tucker of Williamsburg among her literary friends. She exchanged poems with writer Judith Lomax, who penned, “To Mrs. Page of Rosewell, Who averred that poetry was inconsistent with a wedded life.” Margaret Lowther had married Gov. John Page of Virginia and given birth to the last eight of his twenty children. She socialized with George and Martha Washington, hosted General Lafayette during his 1824 visit to Williamsburg, was a longtime friend of Dolley Madison, and was financially assisted by her husband’s closest college friend, Thomas Jefferson, to whom she also dedicated poetry.

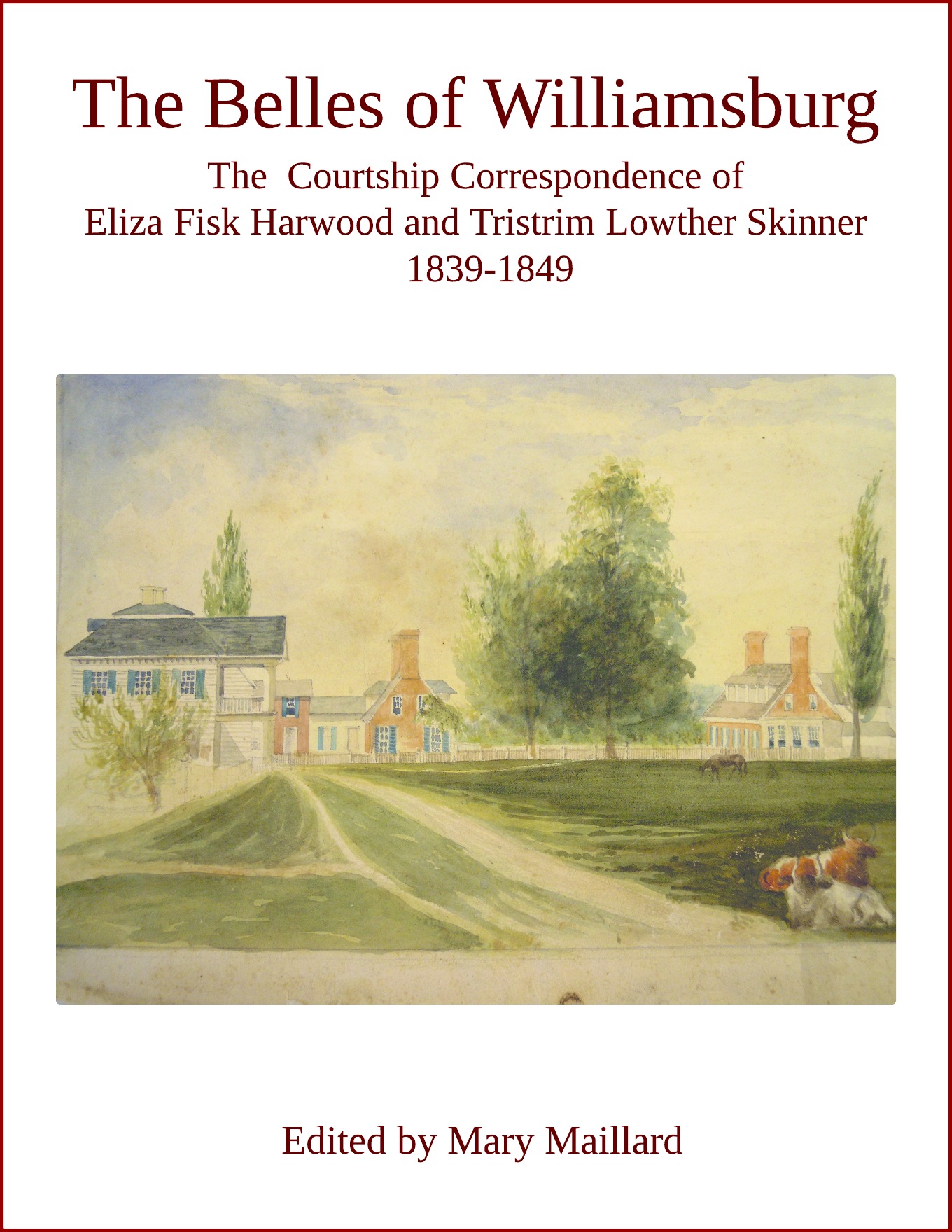

Margaret Lowther Page dedicated poetry to her friend Thomas Jefferson. Portrait of Jefferson by Rembrandt Peale, 1800.

The Page children corresponded regularly with their Skinner cousins, and the Skinners often visited Page’s Rosewell estate in Gloucester county. The youngest of the Pages, cousin Lucy Burwell Page, married mathematics professor, Robert Saunders of Williamsburg, who acted as Tristrim Lowther Skinner’s guardian and academic counselor at the College of William and Mary from 1838 to 1840.[4]

Maria Lowther Skinner’s mother, Penelope “Penny” Dawson – sister of Congressman William J. Dawson and granddaughter of Reverend William Dawson, the second President of the College of William and Mary – was a stunning beauty who inspired gushing admiration of her charms and grace wherever she went. James Iredell Sr. described his young cousin as possessing an “amiable gentleness” and “softness . . . in excess,” a quality which later led to her reputation as a flirt who had a devastating effect on men, young and old.[5] Tom Skinner’s tribute to her is so soaked in superlatives that he would seem to have been badly smitten himself.

“Her person was a rare model of beauty and delicacy: in height, in shape, in complexion, in every feature and line so exquisitely fashioned, that, regarding it in the class of forms to which it belonged, art itself could scarcely suggest an improvement or desire any variation.”[6]

Another, lustier admirer, William Hooper, remarked on Penny’s marriage to Tristrim Lowther in 1786:

William Hooper, signer of the Declaration of Independence, expressed lusty thoughts for Penelope Dawson.

“Mr. Johnston in his letter to me says that Lowther would be unconscionable to refuse to be hanged after enjoying so fine a girl. Might he not add damned too. I mean a temporary damnation. If I had time I would rant a little upon the luscious subject. It sets my old blood afloat with youthful heat & I find a glow about my heart that such a theme could only excite. But I was early taught “Thou Shalt not covet thy neighbour’s” you know the rest. I rejoice that the wedding has been conducted with So much address. It may perhaps pave the way for peace & Security to Lowther.”[7]

Tristrim Lowther’s need for “peace & Security” refers to his arrest in 1783 on charges of being a Loyalist during the Revolutionary War. Known in Edenton as “the Englishman,” he had accompanied his Scottish father, William Lowther, a merchant of Edenton and New York, back to England in 1777, where he remained for several years.

Fifteen-year-old Margaret Lowther and her younger sister Barbara also fled their native North Carolina with their parents. The New York Gazette reported on June 23, 1777, that “Last Wednesday Night Mr. Lowther arrived here with his Family, from Edenton, in North Carolina, being obliged to leave that Province, where the Rebels are persecuting to Death and Destruction every Person, that will not join in the present Rebellion.”[8] Legislation passed during the war enabled the state of North Carolina to confiscate William Lowther’s property in Edgecombe County, Bertie County, and Edenton.[9]

Tristrim Lowther returned to Edenton in 1783 “to the great annoyance of the good inhabitants of said county, and against the laws and Dignity of said State,” according to a warrant for his arrest signed by local leaders.[10] Citizens had drawn up and unanimously approved resolutions to “guard against the evils that might arise from a return of those Persons who withdrew themselves from a defense of the Country, and joined the British in the time of our distress.” These same citizens threatened to tar and feather Lowther.[11]

After receiving the arrest warrant which charged that Tristrim Lowther did not remain in North Carolina to “bear arms in defence of said state” but “gave allegiance to said King,”he was eventually brought to court in Edenton where the jury found him guilty for the plaintiffs and fined him twenty pounds and sixpence. Prejudice against Tristrim Lowther continued for years but in time was supplanted by a high regard for his character and his skills as a lawyer. He eventually was held in such high esteem that Bertie County voters elected him to the House of Commons (1792-1793).[12]

Tristrim Lowther had been tainted by the charge that the elder Lowther had provided the British with intelligence about privateers during the Revolutionary War. In fact, during the British occupation of New York City, William Lowther offered up his Dover Street warehouse for the Royal Army to use as a regimental store, and he also quartered several British officers in his Pearl Street home. Margaret Lowther’s Quaker friend, the “wild and sprightly” Susan Murray, lived nearby and married Loyalist Colonel Gilbert Colden Willett. [13]

George Washington’s entry into New York after the evacuation of the British in 1783. Library of Congress.

When the British evacuated New York in 1783 — looking “grand in their scarlet regimentals,” as Margaret Lowther’s daughter retold the story — one of the officers, Captain Wallace MacLean, secretly married Tristrim and Margaret’s sixteen-year-old sister, Barbara Lowther, and the young couple eloped to Scotland.[14] Captain Wallace MacLean was a son of the Laird of MacLean, immortalized by Dr. Samuel Johnson in his “Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland.”

Halfway across the Atlantic, Wallace MacLean was killed on the ship’s deck when he attempted to break up a fight between two officers. The teen-aged bride-widow, Barbara Lowther MacLean [Mclaine, McClain], continued to the Laird’s estate in Scotland, where she remained for two years until the end of the trial for Captain MacLean’s death. She then inherited her husband’s property, including diamonds, silver and other Scottish heirlooms, and returned to the United States betrothed to a young Edinburgh medical student – none other than her North Carolinian brother-in-law, William J. Dawson.[15]

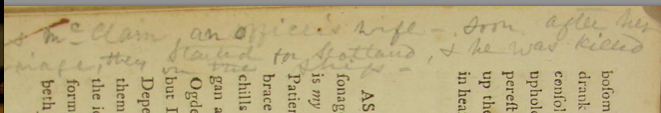

Lucy Burwell Page Saunders’ marginal note in her mother’s published journal. “Mrs McClain, an officer’s wife—soon after her marriage, they started for Scotland, & he was killed on the ship.” Journal and Poems of Margaret Lowther Page, 1790. Special Collections Research Center, Swem Library, College of William and Mary.

William J. Dawson, his mother, sister, and little niece, Maria Lowther, all lived together at “Eden House.” Located in Bertie County near the confluence of the Chowan River and Albemarle Sound, it was one of the oldest and most imposing plantation homes in North Carolina.

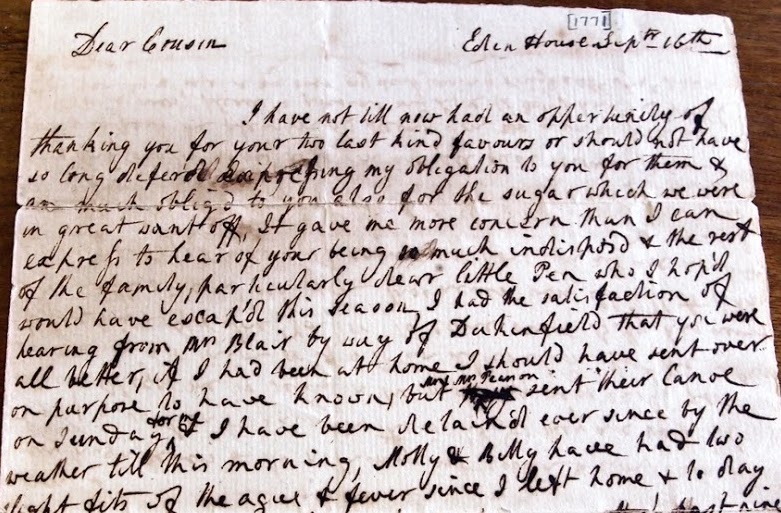

Penelope Johnston Dawson’s 1771 letter from Eden House to her cousin Governor Samuel Johnston. Hayes Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina.

When Maria Lowther married Joseph Blount Skinner she brought with her numerous slaves; real estate, including a half-interest in Eden House; and the prestige that would help her husband to attract clients to his law practice in Edenton. As a cousin of North Carolina Governor Samuel Johnston (President-elect of the United States of Congress Assembled in 1781) and niece of the mistress of Rosewell estate in Gloucester county, Virginia, she could provide Joe B with many advantageous political connections and business contacts. Her lineage overflowed with governors. She was a direct descendant of North Carolina colonial governors Gabriel Johnston and Charles Eden. Maria’s cousins included Iredells, Blairs, Tredwells, Sawyers, and Johnstons, all prominent and successful North Carolina families.[16] When Joseph Blount Skinner — descended from Quaker farmers — married Maria Lowther, he may not have merged two powerful dynasties but, in a social hierarchy where life-long friendships, loyalties, and family background were valued above all else, he may have created one.

For their children — Pen and Trim Skinner — who they were and where they belonged were defined, not by wealth, prestige, or individual accomplishments, but by what southern writer, John Bentley Mays, calls “the map of time and blood.” Their deep roots in Virginia and North Carolina, their descent from royal governors and Quaker planters, their secure place within an agrarian culture imbedded with the ideals of colonial Virginia, their densely inter-woven family connections in a society where blood dictated one’s marriage partner and business associates—all of this taught them, as Mays puts it, “the practical usefulness of blood kinship, woven over time in one place.”[17] That place—the cypress and juniper-lined northern shore of Albemarle Sound; the rivers and creeks that fed it; the fields, swamps, and forests of Bertie, Chowan, and Perquimans Counties; the sandy beaches and fresh breezes of Nag’s Head and Ocracoke; the noisy, smelly, crowded wharves of Edenton and Hertford; the mills, fisheries, farms and plantations that engendered commerce and sustained life — that low country of eastern North Carolina was home.

1]Skinner, Sketch 30.

[2]On the occasion of Penelope Dawson’s 1786 marriage to Tristrim Lowther, her mother, Mrs. Penelope J. Dawson, gave her a two thousand acre estate called Belmont, situated on the middle branch of Salmon Creek in Bertie County, as well as seven slaves and their families. This property and Eden House passed down to Maria Louisa Lowther and her brother William D. Lowther. Penelope Dawson Land Deeds 1783-1786, Series 2, SFP. [3]Tristrim Lowther’s birthdate has been estimated according to his entrance into King’s College, New York. Matricula of King’s College [1774] http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-01-02-0056; The Black Book of King’s College http://www.columbia.edu/cu/lweb/digital/collections/cul/texts/ldpd_7441351_000/pages/ldpd_7441351_000_00000022.html. [4]Margaret Lowther Page died in 1835. “Other Papers,” “Journal and poems of Margaret Lowther Page,” Page-Saunders Papers, Manuscripts and Rare Books Department, Swem Library, College of William and Mary, https://digitalarchive.wm.edu/handle/10288/2226 (October 31, 2013); David S. Shields, ed., American Poetry: The Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 2007), 865, 940; Tristrim Lowther, Northampton County NC, Will Jun 1754, Probate Jan 1759, North Carolina Will Abstracts, 1660-1790; Julian Parks Boyd, Barbara B. Oberg, eds., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson: 1 July to 12 November 1802, Vol. 38 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), 284.[5]Don Higginbotham, ed., The Papers of James Iredell, 2 vols. (Raleigh: Division of Archives and History, Department of Cultural Resources, 1976), 2:96; Nash, “Four Penelopes of Eden House,” 41-48. Nash explained Penny’s flirtatious nature as growing out of her “amiability and unwillingness to hurt” her gentlemen friends.

[6]Skinner, Sketch, 68-71. [7]Donna Kelly and Lang Baradell, eds., The Papers of James Iredell, vol. 3 (Raleigh: Office of Archives and History, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 2003), 196-197. [8]Naval Documents of the American Revolution, Vol. 9, 1777, 158. [9] The Collet Map of 1777 shows the Lowther plantation just north of the entrance of Roanoke River into Albemarle Sound. Hugh Bucknow Johnson, ed., “The Journal of Ebenezer Hazard in North Carolina 1777 and 1778,” North Carolina Historical Review Vol. 36 (1959): 358-381. [10]Warrant for the arrest of Tristram Lowther, November 3, 1783, signed by Jos Blount, Chas Johnson, S. Dickenson and Dick [Mayne]. In private collection, copy provided by Rebecca Drane Warren. [11]Bertie Ledger (Windsor, N.C.), August 16, 30, 1990. [12]Handwritten note on reverse of arrest warrant, November 3, 1783, private collection, copy provided by Rebecca Drane Warren; Robert DeMond, Loyalists in North Carolina During the Revolution (Durham: Duke University Press, 1940), appendices B and C; Papers of James Iredell, 3:155; Skinner, Sketch, 68. [13]The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; American Loyalist Claims, 1776-1835; Class: AO 13; Piece: 030. “Gilbert Colden Willett,” http://www.nysoclib.org/collection/ledger/people/willett_gilbert [14] The Works of Samuel Johnson, LL.D: With An Essay On His Life And Genius by Arthur Murphy, Third Complete American Edition, vol. 2 (New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1851), 654-668. [15]Undated, unsigned handwritten account (written c1880-1886) of the lives of William and Barbara Lowther. The handwriting and prose style of this document strongly suggest Lucy B. Page Saunders as the author. The reference to the current mayor of Norfolk, Mr. Lamb, suggests that this account was written 1880-1885. Page-Saunders Papers, Swem Library, College of William and Mary. [16]Joseph Blount Skinner and Maria Lowther gave their children names from Maria’s family, contravening the usual practice of the husband and wife taking turns naming a child after a beloved family member. That the children’s names – Tristrim Lowther and Penelope Johnston Dawson – refer to Maria’s ancestors and not Joe B’s, indicates that her family might have been considered to be of higher social status. For a thorough discussion of naming practices among the North Carolina planter families see: Jane Turner Censer, North Carolina Planters and their Children (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1984) 32-33. [17]John Bentley Mays, Power in the Blood: Land, Memory, and a Southern Family (New York: HarperCollins, 1997), 184.

Excerpt from A Map of Time and Blood: An Introduction to the Skinner Family Papers 1826-1850 (2014). Kindle, iBooks, or Kobo