In the early fall of 1845, Tristrim Skinner wrote to Eliza Harwood from Boston. “I would be glad if it were not unreasonable in me, to wish that I might live to see our country rid of that institution which keeps it a century behind the age – and so thickly peopled as to render it susceptible of the improvements which abound here.” This oblique comment marks the only instance in a life-time of correspondence spanning thirty-five years in which Skinner specifically mentions his personal views on the subject of slavery. His words, “thickly peopled,” suggest a pro-colonization view to ending slavery.

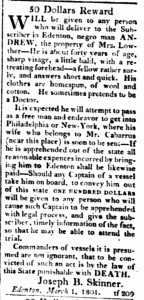

Joseph Blount Skinner’s 1801 runaway slave advertisement. NCRSA, University of North Carolina, Greensboro, N.C.

Tristrim Lowther Skinner may have absorbed many stories of his family’s ever-evolving attitudes towards slaves and slavery, including the early history of his great-grandfather, William Lowther, who owned a slave-running sloop, the Francis,[1] and his other great-grandfather, the Quaker, Joshua Skinner, who disinherited his sons because they married into slaveholding families.[2] Early in his law career, Tristrim’s father — Joseph Blount Skinner — was approached by the Quaker Society of Friends to represent free blacks who had been enslaved under an act of the legislature. Skinner believed this law was wrongly applied and succeeded in regaining the freedom of every individual he represented. Years later, however, acting as attorney for his good friend, Josiah Collins, Skinner was equally committed to the letter of the law; when he spotted Harriet Jacobs’ fugitive uncle, Joseph, in New York, he had him captured and returned to Edenton in chains.

Woven into this fabric of legend and practice, harmony and contradiction, was Tristrim’s elite education at the College of William and Mary where he was exposed to the ingeniously argued pro-slavery ideas of Thomas Roderick Dew and the benevolent paternalism of Nathaniel Tucker as well as heated debates about the American Colonization Society and abolitionism. The Skinner family owned one hundred and eighty-five slaves by 1850 and, on the eve of the Civil War, after Joseph Blount Skinner’s estate division, Tristrim Skinner owned a hundred and twenty-five slaves, more than half of whom were aged twelve and under.

Possibly the strongest philosophical and moral influence on Tristrim Skinner came from his uncle Thomas Harvey Skinner, professor of sacred rhetoric (and founder) at the Union Theological Seminary in New York. In his 1850 Thanksgiving Day sermon on patriotism,[3] Rev. Skinner preached against slavery in the context of republican America and the spirit of “the universal emancipation of man.” He stressed that “Slavery as a system, should find advocates everywhere throughout the whole earth sooner than in this land of freedom. It should, and we hope soon will be, the universal desire that the institution utterly cease.”

Portrait of Thomas Harvey Skinner attributed to Samuel Finley Breese Morse. Oil on canvas. 1852. 76” x 44” (Call number: 1287) Presbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia.

Although Skinner believed emphatically that there “should be no question as to the intrinsic and enormous evil of Slavery, as existing in this country,” he qualified his view in this sermon with the observation that “American slavery, whatever evils it includes or propagates, has law on its side.” Skinner acknowledged the incendiary impact of the Fugitive Slave Law, which had just come into effect three months earlier and was considered “by some to be unconstitutional, by others to be at least inexpedient, and not a few have denounced it as positively immoral, or against the law of God.” He admitted that the law was “a work of simple injustice and inhumanity.” The law was so inflammatory that Skinner saw only two alternative responses to it: “to let the law have its course, or to overthrow the government of the country.” In an attempt to quell violent revolutionary action, Skinner preached due process of law, and urged his listeners to “love the Constitution of their country well enough to suffer for it patiently, even though they love God and virtue too well to do wrong though at their Country’s bidding.” He argued that to “resist the government on account of immorality of the Constitution, is another and a most flagitious immorality.”[4] Skinner preached against the concept of immediatism [5] proposed by militant abolitionists, saying “that abrupt legislation against our slavery, would lead to evils in the country scarcely less, on the whole, than the slavery itself.” He advocated more moderate, gradualist ideas for slavery to be phased out “not by an impetuous driving home of abstract right and truth,” but by a rational, thoughtful, thorough, and critical national discussion, one that would take time and would operate “in the indirect, gentle and suasory method of primitive evangelism.”

Thomas Harvey Skinner’s “sainted friend” since childhood was Eden, an enslaved Methodist minister who lived and preached on Joseph Blount Skinner’s plantation and who refused his freedom. Skinner wrote about his difficult parting with Eden when they were newly converted teenagers in 1811. “Distance afterwards separated us, but did not diminish our friendship. We took pains to cherish and confirm it. By agreement, we daily … remembered each other particularly in prayer. Twice he [Eden] traveled several hundred miles by sea to visit me, and the anticipated pleasure of seeing him was always among the motives of my annual journeys to the South.” Skinner traveled back to Edenton after Eden’s death and preached a memorial lecture on him to “an overflowing house, composed largely of slaves. His text was Rev. 1:6, “Who hath made us kings and priests unto God.” Subject – “The honor which Christianity puts upon man.” More than eight hundred people attended the service. Rev. Skinner’s tribute to Eden appeared in the New York Observer July 28, 1859.

Skinner’s close relationship with slaves and slaveholders in the South, his long residence in New York and Philadelphia (including occasional preaching in the African Presbyterian Church), and his associations with antislavery advocates in the North placed him in an excellent position to act as conduit in assisting Edenton slaves — especially the mixed-race children of planter elites (perhaps his own brothers’ children) — in establishing new lives in the North. In April 1839, Thomas Harvey Skinner arrived for a visit at Joseph Blount Skinner’s house with his abolitionist friend, Thomas Brainerd. In Brainerd’s biography published three decades later, Mary Brainerd paraphrased one of his letters:

“In the evening Dr. Skinner and Rev. Brainerd attended a prayer meeting with the slaves. One old colored man thanked the Lord that they had been spared “to see young Massa Tom come home once more….When they returned to the North, two pretty little white slave girls, with blue eyes and brown hair, were placed under their charge to be sent to school in New England; this being the only mode by which, thirty years ago, their emancipation and education could be secured. So far as good looks, becoming dress and deportment were concerned, these children might have passed for their own through the whole homeward route.”[6]

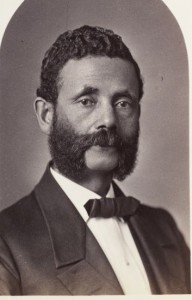

George W. Lowther (1822-1898), Joseph Blount Skinner’s valet, was emancipated in the mid 1840s and moved to Boston where he established a hairdressing business. Active in the abolitionist movement, he was elected in 1878 to the Massachusetts legislature.

Six years later, when Tristrim wrote from Boston the only comment on slavery he would ever make in ink, he not only echoed his uncle’s views but he might well have been affected by the city’s lively anti-slavery movement, by the publications in Boston in 1843 and 1844 of slave narratives, including those of North Carolina natives Moses Grandy and Lunsford Lane [7] and by his more personal knowledge of a former North Carolina slave who had recently moved to the North: his father’s “favourite and faithful Body Servant,” George W. Lowther.[8] There was no family estrangement with George Lowther. Old Joseph Blount Skinner was proud enough of George’s accomplishments in Boston to describe him in 1850 as “much respected by Gentlemen and in good business.” By the late ‘40s Tristrim would not only have been aware of George Lowther’s abolitionist activities in Boston and his association with future slave-narrative author, Harriet Jacobs — whose book Lowther endorsed — but he would have viewed Harriet Jacobs’ difficult situation from yet another, possibly more sympathetic perspective than that of other slave-owners: Tristrim’s aunt Annie (nee Sawyer) Lowther was the white aunt of Harriet Jacobs’ two children, Louisa and John S. Jacobs..

That Tristrim’s views of slavery were conflicted and complex is revealed by the depth to which George Lowther had become entrenched in his psyche. In late 1861, when he had become Captain Tristrim L. Skinner of North Carolina’s Albemarle Guards, Trim dreamed a remarkable dream—that George Lowther had returned to Edenton to “espouse the Southern cause.”

[1] Walter E. Minchinton, “The Seaborne Slave Trade of North Carolina,” North Carolina Historical Review 71 (1994): 1-61; slave bill of sale from William Lowther, Robert Hardy, and Andrew Little to Francis Nixon on behalf of John Moore, November 28, 1767, Book H, No. 32, Perquimans County court records http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~wkkoerber/Nixon/LandRecordNC39.html (December 5, 2013). [2]William Wade Hinshaw, Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, vol. 1 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing, 1969), 17. [3]Thomas H. Skinner, Love of Country: A Discourse, Delivered on Thanksgiving Day, December 12, 1850, in the Bleecker Street Church (New York: E French, 1851), 23-30. [4]Skinner was almost certainly aware of Thoreau’ s arguments on civil disobedience (“Resistance to Civil Government,” Aesthetic Papers, Elizabeth Peabody, 1849) but found no justification for breaking unjust laws short of revolution. [5]Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who believed that the U.S. Constitution was a pro-slavery document, embraced immediatism in the early 1830s out of frustration with the slow pace of reform in the West Indies. He, along with Wendell Phillips, Lucretia Coffin Mott, and John Brown, did not have confidence in the gradual emancipation of slaves through colonization and political reform. “Immediatism,” http://www.answers.com/topic/immediatism-1 (October 31, 2013). [6] Mary Brainerd, The Life of Rev. Thomas Brainerd, D.D.: For Thirty Years Pastor of Old Pine Street Church, Philadelphia (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1870), 176. [7] William L. Andrews, ed., North Carolina Slave Narratives (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 9. [8] George W. Lowther (1822-1898) was privately educated in the Skinner household and, after his emancipation, moved to Boston and ran a successful hairdressing business. Will of Joseph Blount Skinner, November 16, 1850, SFP; Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, 312; Mary Maillard, “George W. Lowther,” blackpast.org.

Note: Excerpt from A Map of Time and Blood: An Introduction to the Skinner Family Papers 1826-1850 copyright © Mary Maillard 2014