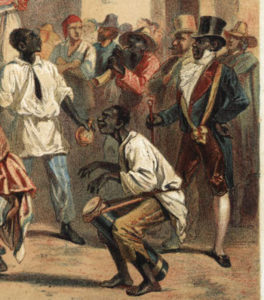

African-American abolitionist, Martin R. Delany (1812-1885), included a detailed description of Kings Day in Havana (c. 1853) in his novel, Blake: Or the Huts of America (1859-62). “I am indebted,” he wrote, “for the following description of the grand Negro festival to a popular American literary periodical, given by an eyewitness to the exhibition:

“For the week preceding the sixth of January, the native African servants of Havana are in a state of intense excitement. Their masters and mistresses are begged for every spare feather, flower, bit of tinsel, ribbon, or finery of any description whatever; their pocket money is spent on the conventional trash consecrated to the occasion; and every leisure moment is consecrated to preparing for that great day on which they may at least fancy for a few hours that they are free. In all the year, this is the only day the black can call his own; the law gives it to him, and no master has the right to refuse his slave permission to go out for the whole day.

“At last the important day arrives; the dawn is ushered in by salvos of artillery from Moro Castle–the Negroes pour out of the city gates in crowds to assemble at the places where they are to dress–dainty dressing rooms are they–and the delicate ear is agonized by sounds proceeding from the musical instruments of Africa. They generally assemble according to their tribes. The Gazas, the Lucumis, the Congoes, and Mandingos, etc., in separate parties. One party ordinarily consists of from ten to twenty. These are about half a dozen of principal actors, and the rest hang around and are ready to do any extra dancing or shaking that may be required. Women there are too, in plenty–their dresses ‘low in the neck and high in the arms,’ covered with gay ribbons and tinsel flowers–that dance all day long for the pure love of the fun, joining first one party and then another, constant to none, and therefore have no right to a portion of the money collected.

“Their place of rendezvous on the King’s Day being the grand square or Plaza de San Francisco, called after the church and convent of that name.

“There are three principal personages that appear, with but slight variation of costume, in every group, no matter to what tribe it belongs. They are always chiefs, princes or prophets, or if these elevated individuals are not sufficiently numerous to head the numberless parties, the highest in rank is always chosen to wear the regal African paraphernalia *** The king is dressed in a network of red cord, through the interstices of which glisten oddly enough square inches of the royal black skin. Round his waist is an immense hoop, with a thick drapery of horsetails with every color of the rainbow, with many hues not found therein.

“Another has a hideous mask surmounted by horns. He is the prophet of the tribe, and is sometimes supposed to be gifted with magical powers–a full belief in charms being a part of the Negro’s native creed. *** This Obesh or Jumbo butts with horns, yells, and performs various antics that impress deeply the surrounding Negroes. If a white person pretends to be alarmed at the unearthly sounds or sights, it is, of course, a great triumph.

“Around the feet of the principal performers are fastened branches of horsehair, that divide the mind between Mercury and a bantam cock.

“Placing themselves in the attitudes of kangaroos, they go through a series of shuffling, screwing, and shaking that utterly defies any description. It cannot be called dancing, for Sorocco would disown it; neither can it be called convulsions, for the doctors would pronounce them perfectly healthy. St. Vitus himself would be puzzled what to call it, though he could not be gratified at the favor of his votaries.

“All day long they keep up a movement of some kind, either dancing or waltzing to an almost incredible degree. The parties roam all over the city, stopping in front of the principal houses, or before the windows in which they see ladies and children. They have also their favorite corners, and there they will go through with fifteen or twenty minutes violent agitation, during which the perspiration pours off their faces, and one unaccustomed to the sight is momentarily expecting to see them fall exhausted to the ground, perhaps never to rise again. The only stoppage, however, is when that elaborately dressed personage with a cane, so beruffled and beringed, hands round the box to the spectators for “pesetas” and “medios.” He is the steward of the party, and after all is done, he produces the money which pays for the room in which they hold their ball at night–all night indeed, for they keep it up till morning.”

Kings Day celebrations were similar to other African-Caribbean drum-dance parades, called variously Junkanoo, Jankunu, or Jonkonnu, that were held on Sundays or fiestas and were the only source of entertainment permitted to the slave population. The ritual Dickie Galt described in this letter (unfamiliar to him and to most Americans) was also practiced in eastern North Carolina slave celebrations known as John Kooner, John Koonah, or John Canoe at Christmas and New Years. Rev. Moses Ashley Curtis described the Wilmington, N.C. “Kuners’ in 1830: “The negroes have a singular custom here…of dressing out in rags & masks, presenting a most ludicrous appearance imaginable. They are accompanied by a troop of boys singing, bellowing, beating sticks, dancing & begging….One of them was completely enveloped in strips of cloth of every colour.” The Christmas tradition of John Konnering was practiced in Edenton until the 1880’s. Tristrim Skinner would have been well acquainted with it, and his new wife, Eliza, had probably witnessed a similar celebration by the time she received this letter.

Martin R. Delany, Blake: Or the Huts of America (1859-62) Floyd J. Miller, ed. (Boston: Beacon Press 1970), 299-301; Clifford L. Staten, The History of Cuba (Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 2003), 25; Bertram Wyatt-Brown, Southern Honor: Ethics and Behavior in the Old South (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982), 444; Guion Griffis Johnson, Ante-Bellum North Carolina: A Social History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1937), 553.