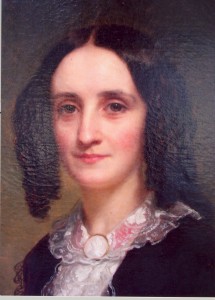

A younger daughter of the eleven children of John and Susan Harwood, Eliza Fisk Harwood (1827-1888) did not grow up with the rest of her family in the naval port of Norfolk, Virginia.[1] Her mother had “given” Eliza as a baby to her niece, Mary Ann Galt, as part of a southern tradition in which a childless aunt, sister, or other female relative would raise girls, lavishing them with their full attention and affection.[2] Eliza called her cousin “Godma;” Mary Ann Galt gave Eliza her maiden name, so Eliza often went simply by the name Eliza Fisk.[3] Although she visited her Harwood family in Norfolk occasionally, Eliza considered herself very much a Williamsburg girl. She attended school in town – until the schoolhouse burned down in 1842 – took part in services at Bruton Parish Church, and participated fully in all aspects of Williamsburg’s elite society, including summering with the town’s best families at Fauquier Springs.

Fauquier White Sulphur Springs, also known as Warrenton Springs, in the mid 1850s. Merritt T. Cooke Memorial Virginia Print Collection, 1857-1907, Accession #9408, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library.

Eliza and her beau — Tristrim Skinner of Edenton, North Carolina — had much in common: a deceased parent they had never known, a surviving but mostly absent parent, and loving cousins acting in loco parentis. They both had blood ties to the Williamsburg aristocracy. Through the Pages and Randolphs, they were even distantly related to each other[4] and were social equals in a genteel world that valued family, education, piety, and the social graces more than economic status. Eliza, whose grandmother was a Burwell, was connected to a wide network in Williamsburg and Yorktown, including the Nelsons, Harrisons, Armisteads, Meades, Southalls, Littletons, Tazewells, as well as the Lees of “Chiskiak” and the Harwoods of Warwick County.[5]

Market Square in Norfolk, Virginia, in 1845. Eliza shopped at Paul & Pegram, shown at lower left. Historical Collections of Virginia.

Her long dead father had owned a warehouse in the Navy Yard and Harwood’s Wharf in Norfolk where he had organized freight and passage, sold wholesale goods, and worked as government appraiser.[6] Eliza’s grandfather, Col. Edward Harwood, had squandered the immense family fortune of his father, leaving his children to make their own way, by marriage or business, in an urban professional middle class. Her closest brother, Henry, worked as a bookkeeper in Norfolk; her brother, William, taught school in Richmond; her sister, Maria, also a teacher, married newspaper editor and lumber inspector, Charles H. Beale; another sister married a teacher; and another an auctioneer.[7]

At the age of nineteen, Eliza signaled to Tristrim Skinner and the rest of the world both her continued selectivity and her readiness to give up the tiresome life of a belle. At Fauquier Springs, on display among the most refined of southern ladies and gentlemen, Eliza attended a fancy dress ball costumed as a bride, “being the simplest and the prettiest I could wear. If only the groom had presented himself – Many did, but they were not the right one.” In the theatrical, fantastical, competitive climate of the springs, where tableaux, tournaments, hunts, and costume balls were performed and experienced by the visitors, Eliza’s choice of costume epitomized her idealized romantic goal of marriage as well as her refusal to follow the script and play a part.[8]

Eliza and Trim were married on February 19, 1849, in a modest ceremony in Williamsburg, performed by their dear friend, the former College professor, Reverend Charles Minnigerode. Eliza had entered society as a bridesmaid at Minnigerode’s wedding and now—six years later, and with his blessing—she concluded her life as a belle.

Excerpted from Mary Maillard, ed., The Belles of Williamsburg: The Courtship Correspondence of Eliza Fisk Harwood and Tristrim Lowther Skinner 1839-1849 copyright © Mary Maillard.

[1] Eliza’s parents, Susan Hollands Gilbert (1793-1858) and John Robbins Harwood married on February 1, 1811. Their eldest child, William Bacon Harwood, was born the same year. Their second son, Reynier [Reynear] Gilbert Harwood, died when eight months old from exposure while in a boat fleeing Norfolk during the British bombardment in June 1813. Eliza Fisk Harwood’s daughter, Marian Fisk Skinner (1853-1941) maintained that the second, third, and fourth children – Reynier, John Dabney (who was later lost at sea), and sister, Virginia – were triplets.

[2] TLS to EFH November 19, 1848; February 8, 1849, SFP. As historian Catherine Clinton notes, such an arrangement was not unusual. Mothers with several girls might send one of them to a childless sister or sister-in-law, an arrangement that benefited all involved, most particularly the adopted daughter, who was “doubly mothered.” Catherine Clinton, Plantation Mistress, 53-54. Frederick Blount Drane, “adopted” inscription on back of daguerreotype of Mr. and Mrs. Henry Harwood, private collection.

[3] Nathaniel Beverley Tucker to Lucy Tucker, May 11-12, 25, 1843; Charles Minnigerode to Cynthia Tucker, July 6, 1843, Tucker Coleman Papers, Swem Library, College of William and Mary. Eliza’s bound music books show several examples of her signature as Eliza Fisk, private collection, Elizabeth Matheson.

[4] Armistead C. Gordon, “The Stith Family,” William and Mary Historical Quarterly 22 (July 1913, January 1914): 44-51, 197-208; Armistead C. Gordon, “Further Notes on the Stith Family,” William and Mary Historical Quarterly 22 (April, 1914), 273-275; Ronald L. Hurst, “The Peyton Randolph House Restored,” Antiques Magazine, January 1, 2001; Richard Channing Moore Page, Genealogy of the Page Family in Virginia (New York: Press of the Publishers’ Printing, 1893), 78-81; Francis L. Berkeley, “Berkeley Manuscripts,” William and Mary Historical Quarterly 6 (January 1898): 135-152; Nathaniel Claiborne Hale, Roots in Virginia: An Account of Captain Thomas Hale, Virginia Frontiersman, His Descendants and Related Families (Philadelphia: n.p., 1948) 40.

[5] Sheila R. Phipps, Genteel Rebel: The Life of Mary Greenhow Lee (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2004), 2; Lyon G. Tyler, “Lightfoot Family,” William and Mary Historical Quarterly 2 (April 1894): 259-262; 3 ( October 1894): 107-108; Lyon G. Tyler, “The Lee Family of York County,” William and Mary Historical Quarterly 24 (July 1915): 46-54; Richard Channing Moore Page, Genealogy of the Page Family in Virginia (New York: Publishers’s Print Co., 1893), 78-81; Lyon G. Tyler, “Notes by the Editor,” William & Mary Historical Quarterly 2 (April 1894): 230-236; Armistead C. Gordon, “Burwell Family Records,” William & Mary Historical Quarterly 15 (October 1906): 93; John Marshall, “Burwell Family,” April 15, 2000, http://homepages.rootsweb.com/~marshall/esmd42.htm (October 31, 2013); “Personal Notices From The Virginia Gazette, 1736-1738,” William and Mary Historical Quarterly 5 (April 1897): 240-244.

[6] John C. Emmerson, Jr., comp., The Steamboat Comes to Norfolk Harbor: And the Log of the First Ten Years 1815-1825 (Portsmouth, VA: n.p., 1947), 377; Congressional Serial Set (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1831), 231.

[7] “Col. William Harwood’s Will,” Newport News Warwick Historical Preservation Association, http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~vannwhpa/vannwhpa/col__wm__harwoods_will.htm; “Henry Harwood,” 1860 U.S. Census, Norfolk, Norfolk, Virginia, Roll: M653_1366; Page: 542; “William B. Harwood,” 1850 U. S. Census, Richmond, Richmond, Virginia, Roll M432_951, Page 407B; “Maria Beale,” 1870 U.S. Census, Norfolk, Norfolk, Virginia; “Virginia Addington,” 1850 U. S. Census, Norfolk, Norfolk, Virginia, Roll: M432_964; Page 110B.

[8] EFH to TLS August 22, 1846, SFP. Historian Charlene M. Boyer Lewis, in her excellent study of life at the courting grounds of the Virginia Springs, explores southerners’ fascination with romanticism, medieval chivalry, olden times, and exotic lands, and notes that the events were more than just games and imitation: people “were playing out their own fantasies.” The tournaments allowed men and women “to live their romanticized ideal of themselves in full by playing the roles of maidens and cavaliers.” Charlene M. Boyer Lewis, Ladies and Gentleman on Display: Planter Society at the Virginia Springs 1790-1860 (2001), 177-186, 200-208.